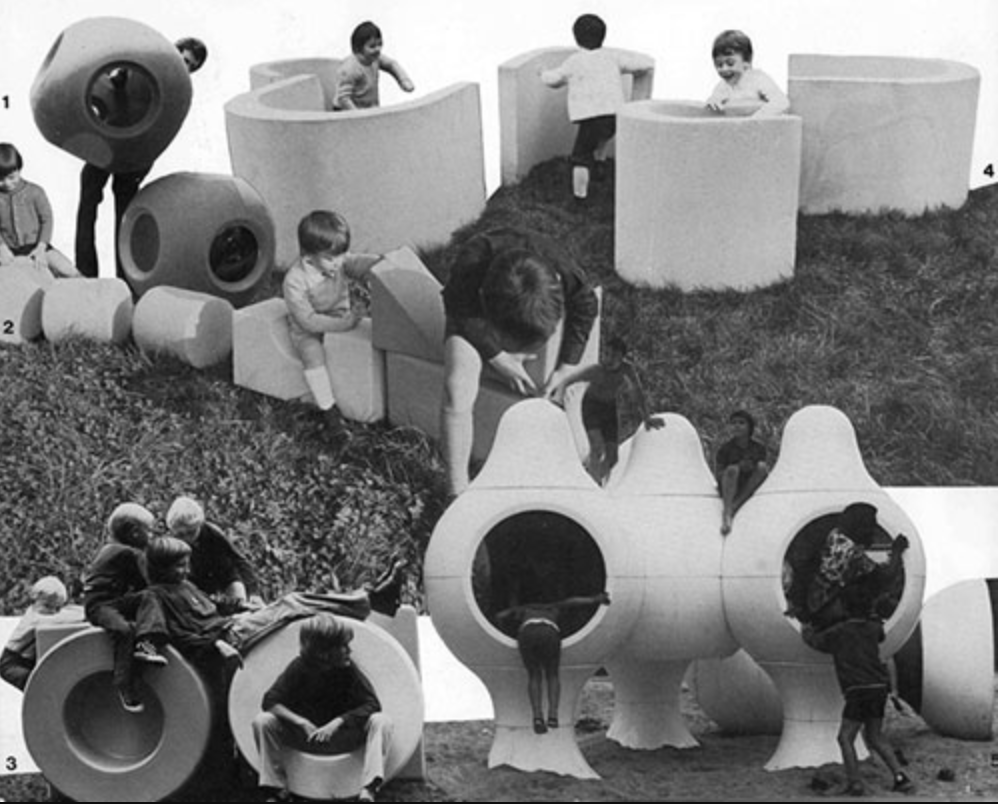

Playgrounds, Les Simonnet, 1960.

The artist duo Les Simonnet, made up of Pierre and Annie Simmonet, have made their mark on the French art scene with a singular body of work combining sculpture, design and playful art. Their particularity: designing monumental sculptures that take the form of children's games, at the crossroads of art and urban furniture. Working since the 1960's, Les Simonnet were early interested in the relationship between art and everyday life, in particular by integrating the child as a central player in public space. For them, art shouldn't just be contemplative; it can - and must - be manipulated, explored and experienced. Their work is thus distinguished by a strong educational and social dimension, in keeping with their desire to open up art to all.

Their sculptures, often colorful, rounded and modular, are designed to awaken imagination, curiosity and motor skills. Inspired by simple geometric shapes, supple volumes and resistant materials, they designed numerous playful modules installed in schools, nurseries and public squares, notably in France in the 1970's and 1980's. These works transform playgrounds into genuine spaces for artistic experimentation, while respecting children's needs and dreams.

Through their creations, the Simonnet pose an essential question: what if play were a form of artistic expression in its own right? By blurring the boundaries between sculpture and play,